Antonio C. IxtamerTz’utujil Maya, San Juan la Laguna, b. 1968Pascual Abaj / The Rock PascualOil on canvas, 1990, 18” x 15”Arte Maya Collection

There are literally hundreds of sacred sites where Maya practice their rituals. Many are outside of the towns in the forested hills, often where there are prominent rocks, water sources, or groves of trees. These people are at Pascual Abaj, one of the most sacred of these sites outside the town of Chichicastenango. The brilliantly lit Catholic church at the center of town contrasts with the ritual secretly performed at night in the forest. Despite more than 500 years of dominance by the Catholic Church, the Maya continue to practice important aspects of their religious traditions.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Paula Nicho CúmezKaqchikel Maya, San Juan Comalapa, b. 1955Process and Vision of the Peace AccordsOil on canvas, 2007, 39” x 29”Helen Moran Collection

This splendid painting of a weaver spinning thread for a new fabric suggests hope for a better future after a dark past. Paula said: “To me, Guatemala has been drowned, as in the sea.… The only thing that remains for us is to once again weave the country, without forgetting our histories, which we carry in our skin and in our voices.” Her words reflect hope that the 1996 signing of the Peace Accords to end the 36-year Guatemalan internal conflict would finally end five centuries of subjugation, genocide, and discrimination against the Maya people, and enable the weaving of a new chapter for the Maya and Guatemala.

Read the Complete Text |

|

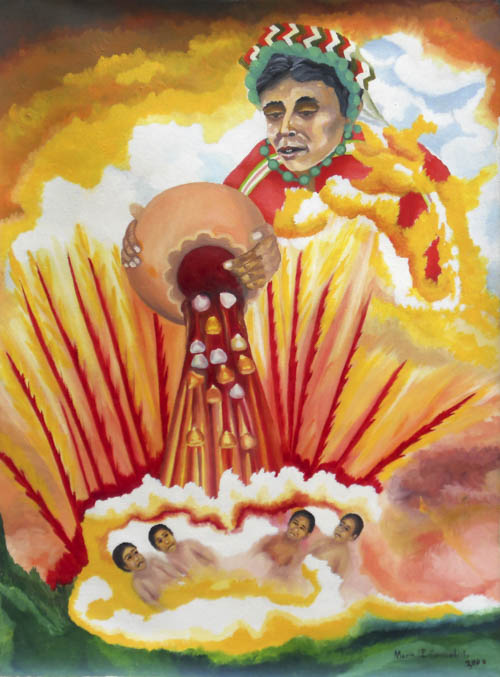

María Elena CurruchicheKaqchikel Maya, San Juan Comalapa, b. 1959Grandma Xmukane’OOil on canvas, 2008, 24” x 18”Helen Moran Collection

The Popol Wuj is considered the holy book of the Maya and tells of the creation of the world. In this book, K’abawila’ were beings endowed with energies and power who created all the plants and animals but failed in their attempts to create human beings. Just before the first dawn when light flooded the world, the animals brought ears of yellow and white corn to the K’abawila’. They gave the corn to Grandmother Xmukane’, who ground the corn nine times, then formed four men and women out of the cornmeal.

The painting shows this close linkage between humans and corn, the most important food source of the Maya.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Paula Nicho CúmezKaqchikel Maya, San Juan Comalapa, b. 1955Ruk’ux Kaj / Heart of the SkyOil on canvas, 2010, 15” x 20”Helen Moran Collection

For the Maya, the earth, the sky, and water are living things with a spirit and energy just like plants, animals, or people. Paula says of this symbolic painting: “There are three energies: Ruk’ux ya’el, Heart of the Water; Ruk’ux ulew, the Heart of the Earth, and Ruk’ux kaj, the Heart of the Sky. These are the energies that protect us and provide us with security and nourishment, the way a mother does.” For the Maya, Heart of the Sky means the spirit or animating energy of the sky.

Read the Complete Text |

|

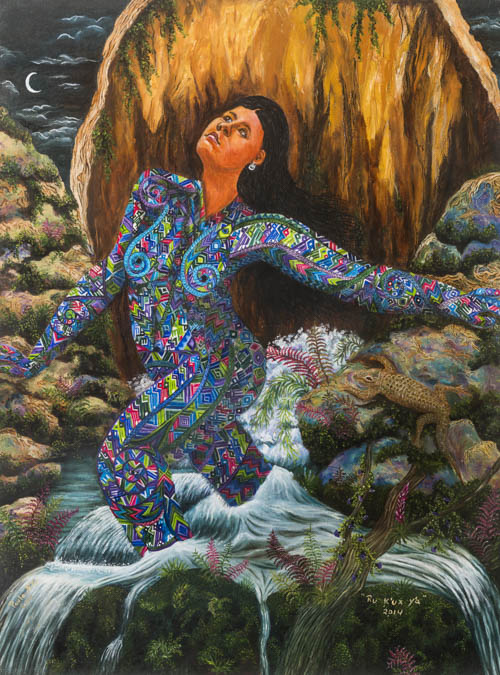

Paula Nicho CúmezKaqchikel Maya, San Juan Comalapa, b. 1955Ru K’ux Ya’ / Heart of the WaterOil on canvas, 2015, 32” x 24”Helen Moran Collection

In this symbolic painting we see a woman emerging from a mountain spring. She represents the heart, the essence, of the spirit of water. For the Maya, such things as the earth, the sky, and water, are living things with a spirit just like plants, animals, or people. Paula explains: “These are the energies that protect us and provide us with security and nourishment, the way a mother does. Our Mother Earth is generous and wants to see us grow. She gives us water from her breast and lets us live in her body as her memory.”

Read the Complete Text |

|

Paula Nicho CúmezKaqchikel Maya, San Juan Comalapa, b. 1955Our Mother EarthOil on canvas, 2010, 24” x 32”Helen Moran Collection

The Maya have a deep connection with Mother Earth and think of the Earth as sacred and as a living being. In this painting Paula Nicho Cúmez personifies Mother Earth, depicting her as a woman wearing the huipil (traditional blouse) of San Juan Comalapa, the Maya town where Paula has always lived. We see Mother Earth not only protecting the town, but also embracing the two nearby mountains that Paula personifies by giving them faces of wise old women. On the two mountains Paula has painted stylized birds, including the endangered quetzal, found on many Maya weavings.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Respecting Mother EarthOil on canvas, 2012, 15” x 13”Arte Maya Collection

The ritual site of Chi Kaqajaay, near the San Pedro volcano, lies within a grove of ancient trees. The Maya believe that anyone who cuts down one of these trees will be cursed. In Pedro <’s painting a couple are honoring a sacred tree by burning incense and candles. During the month of Wayeb (the last five days of the Maya solar calendar), the Maya traditionally abstain from their normal work and use this time for honoring Mother Earth by performing ceremonies at springs, sacred rocks or boulders, and as in this painting, at ancient trees.

Read the Complete Text |

|

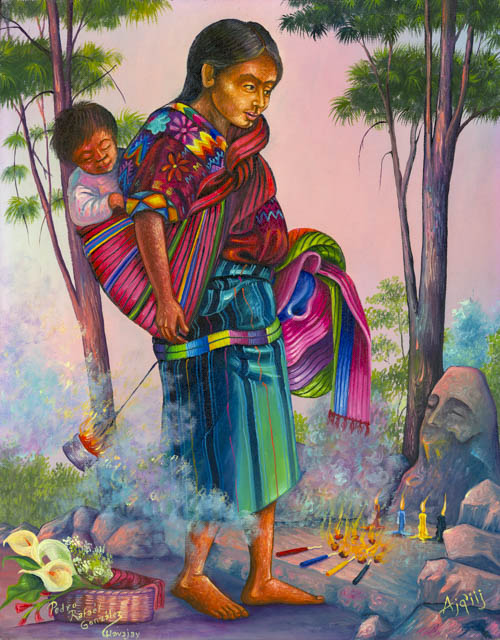

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Ajq’iij / DaykeeperOil on canvas, 2002, 14” x 11”Arte Maya Collection

This painting portrays an ajq’iij, a spiritual guide or daykeeper, performing a ritual to use the Maya lunar calendar to measure time and space. The guide can interpret the energies of each day to help others to understand their problems, needs, and goals. There is often a sign at birth that the newborn is destined to become a spiritual guide and, when the person becomes an adult, he or she is called to become an ajq’iij through their dreams. Their mission is to help guide people to live in harmony with the cosmos.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Antonio C. IxtamerTz’utujil Maya, San Juan la Laguna, b. 1968Members of a Religious Brotherhood in Sololá, GuatemalaOil on canvas, 1988, 16” x 10”

|

|

Oscar Fernando Saquic NixK’iche’ Maya, Chichicastenango, b. 1989Ceremonial Staff and Figure of the TzijolajAcrylic on wood and gourd, 2020, 16” x 2.75” diameterHelen Moran Collection

La vara is a ceremonial staff that serves as a symbol of the power of the ancestral authorities. Each year the staff is transferred to the new authorities named by the cofradías (Catholic religious brotherhoods). This staff from the town of Chichicastenango is topped by a painted gourd and a small wooden sculpture known as the Tzijolaj. The Tzijolaj is a mythical figure transmitted by the Maya ancestors, but in an example of religious hybridization, is depicted as Saint James the Greater mounted on a horse (Santiago de los Caballeros).

Read the Complete Text |

|

Lorenzo González ChavajayTz’utujil maya, San Pedro la Laguna, 1927–1996Entrega de Cofradías, Costumbres del Año 1935Oil on canvas, 1995, 31” x 32”Arte Maya Collection

Every year there is a change in the individuals who perform different roles in the religious brotherhoods known as cofradías. The outgoing official gives the power and emblems of office to the incoming official, and the pair embrace. In this painting, officials are handing over such objects as the vara (the staff of authority); the adzes that cofrades used for digging graves (a responsibility of the brotherhoods in the past); and the censers for burning incense. This was the last painting Lorenzo completed before his death.

Read the Complete Text |

|

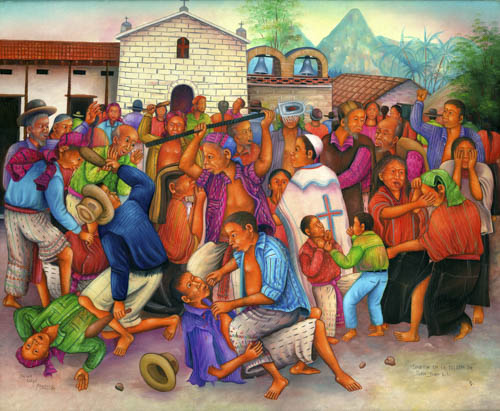

Julián Coché MendozaTz’utujil Maya, San Juan la Laguna, b. 1975Division in the Church of San Juan la LagunaOil on canvas, 1994, 20” x 24”Arte Maya Collection

Division in the Church depicts a 1987 clash between supporters of a foreign Catholic priest and the Maya parishioners of San Juan la Laguna. The conflict arose from the attempts of the priest to purify the villagers’ religious practices. He particularly disliked the religious brotherhoods (cofradíaaas) and what he considered the pagan cult of Maximón (a Maya folk saint). The priest had refused to perform the Eucharist for villagers, claiming they were unworthy. In 1987, tensions between the priest and the parishioners erupted into the violence depicted in Julián’s painting.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Waxaq’ii B’atz’ / Maya New YearOil on canvas, 2016, 32” x 42”Helen Moran Collection

This painting depicts a rite for the ceremonial New Year of the ajq’ijaa’ (spiritual guides) performed on behalf of the people of San Pedro la Laguna. The first day of the Maya New Year is called Waxaq’ B’atz’ or 8 B’atz’. This is the day for the community to give thanks and to be revitalised. Read the Complete Text |

|

Oscar Fernando Saquic NixK’iche’ Maya, Chichicastenango, b. 1989El Cholq’ij / Explainer of Days (Calendar)Acrylics on a clay comal, 2020, 21” diameterHelen Moran Collection

Glyphs of the twenty days of the cholq’ij (the 260 day Maya ceremonial calendar) are painted on an earthenware griddle (comal) traditionally used to cook tortillas. Each day will have one of thirteen levels of energy, and during a ceremonial year, each of the twenty day glyphs passes once through all thirteen levels of energy. The cholq’ij informs the work of the ajq’ijab’ (spiritual guides), iyomab’ (midwives), and k’exelomab’ (women preparing to become midwives). These spiritual professions use the ceremonial calendar to help people and communities understand their destinies with sacred time and space.

Read the Complete Text |

|

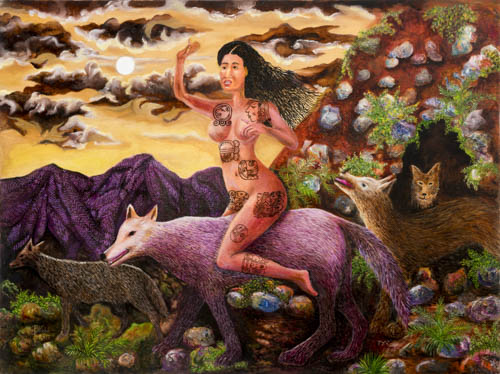

Paula Nicho CúmezKaqchikel Maya, San Juan Comalapa, b. 1955Tz’i’ / Dog or WolfOil on canvas, 2017, 24” x 32”Arte Maya Collection

Tz’i’ is the tenth day of the Maya ceremonial calendar. Its nawal, or energy and protective spirit, is the dog or wolf. In a spiritual context, this day signifies authority and judgment. The glyph for tz’i’ is painted on the shoulder of the woman’s upraised arm. Read the Complete Text |

|

Salvador Cúmez CurruchichKaqchikel Maya, San Juan Comalapa, b. 1945Los Nawales, Altar de Tzi’ / Guardian Spirits, Altar of the Dog or WolfOil on canvas, 2018, 18” x 24”Helen Moran Collection

Nawal, also written nahual, is the Maya word for a guardian spirit. The Maya believe that each person is born with a nahual, usually an animal or bird that is determined by the person’s astrological birthday. This energy and spirit is found in all things throughout the world. Thus, a mountain has its guardian force or spirit, the wind has a spirit, and all living plants have a spirit. In this painting a Maya spiritual guide communicates with nawales, or protective spirits, at the altar of the dog or wolf.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Nim raqan q’iij nim raqan aaq’a’ / EquinoxOil on canvas, 2015, 21” x 25”Arte Maya Collection

Around the equinoxes marking the start of spring and of autumn, the Maya have great celebrations with seed-blessing rituals for the next planting. These rituals are to maintain the balance between humans and the universe. In this painting, the people of San Pedro la Laguna are blessing ears of the four colors of corn. Candles of four colors melt in the sacred fire.

The ancient Maya were extremely accurate astronomers. Even today, Maya day keepers perform rituals at archaeological sites like Uaxactun, where on the equinox the sun lights up a room at the top of the pyramid.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Nawal Ixim / Goddess of CornOil on canvas, 2012, 15” x 13”Arte Maya Collection

In this painting we see Pedro <’s personification of maize (corn). When the Maya perform a ritual to bless their seed for the next year’s planting, they commune with the spirit of corn during the cere-mony. Corn is the staple of the Maya diet and is part of the Maya creation story as expressed in the Popol Wuj. In that story, the hero twins defeat the gods of the underworld, tricking them by dying and coming back to life. Each year, the twins come up from the underworld and are born as ears of corn, only to die again, and the cycle repeats itself.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Blessing of the CornOil on canvas, 2005, 30” x 40”Helen Moran Collection

Corn (maíz) is the most important food source for the Maya. Pedro < commented about his work that: “We Maya carry in our blood the knowledge of corn. This is why I put men of corn in this painting—because we go along from our mother’s womb until our death working on the harvest of corn.” The painting shows a ceremony in the town of San Pedro la Laguna to bless the seeds that will be planted on the hillsides. An enormous pot of atol (a thick, hot drink made of corn) has been prepared by the women to share with the community.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Purification of the SoulOil on canvas, 2007, 24” x 20”Arte Maya Collection

The three men in this painting wearing the tzutes (head scarves) are ajq’ijaab’ (Maya spiritual guides) gathered with other community members for a ritual at a spiritual site. Pedro Rafael explains that the ajq’iij assists in cleansing the participants of their past problems and bringing them in line with nature so that their future activities will succeed. Traditional offerings for Maya rituals are included in the depiction: colored candles, incense, alcohol, and the fire that consecrates the space. The participants are wearing the attire of San Pedro la Laguna, a town at the base of the San Pedro Volcano.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Maltyoxiineem / Blessing the ChildrenOil on canvas, 2004, 30” x 40”Helen Moran Collection

A Maya spiritual guide from Chichicastenango presides over a ceremony at a sacred location in San Pedro la Laguna. People of different villages wearing their distinctive clothing have brought their children to be blessed. This Maya ceremony for bringing children into the community is similar to the Christian baptism ceremony except that fire rather than water is used for purification. Maltioxiineem means “Gratitude to God,” and the painting depicts the presentation of children to the Ajaw, the Lord of the Sky and the Earth, in thanks for bestowing children upon their families.

Read the Complete Text |

|

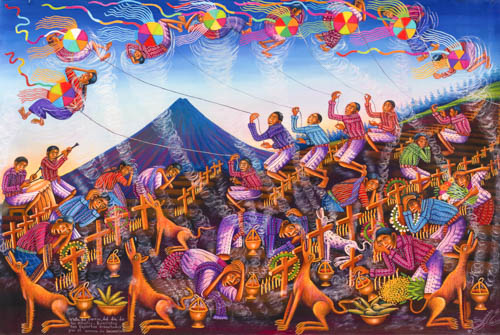

Diego Isaías Hernández MéndezTz’utujil Maya, San Juan la Laguna, b. 1970What Dogs See on the Day of the Dead:

|

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Qab’aniikiil / Our Identity (Three Maya Towns)Oil on canvas, 2013, 36” x 60”Arte Maya Collection

Represented here are Maya spiritual traditions and life from three towns. Tz’utujil-speaking Santiago Atitlán is on the left; Tz’utujil-speaking San Pedro is in the center; and K’iche’-speaking Chichicastenango is on the right. Also shown are the forest and animals around the pre-Invasion temple of Tikal. Everyday activities depicted include the market and church of Santo Tomas in Chichicastenango; a man having a fracture set by a healer; a woman weaving outside a traditional house; and people harvesting coffee and sugar cane. Spiritual traditions represented include musicians playing during a ceremony blessing the corn; a ceremony being held for the folk saint Maximón; deer dancers leading a village procession; and Maya daykeepers performing a ritual at the rock of Pascual Abaj.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956The Footsteps of Yesterday and Today: A TriptychOil on canvas, 2001; three panels, each 30” x 40”Arte Maya Collection

The triptych Footsteps of Yesterday and Today depicts a procession in San Pedro la Laguna on the feast day (June 29) of the town’s patron, Saint Peter. The triptych shows how the town, the people in their traditional dress, and the procession would have looked in the middle of the twentieth century, a few years before Pedro < was born. |

Read the Extensive Text for all Three Panels of the Triptych |

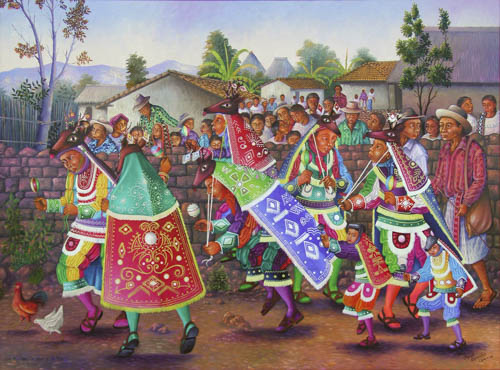

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956The Footsteps of Yesterday and TodayPanel one of a triptych: pre-Hispanic traditionsOil on canvas, 2001, 30” x 40”Arte Maya CollectionThe left panel of the triptych shows the Deer Dance that has roots predating the Spanish Conquest. Performing this dance on the day of the patron saint of the town, and dedicating the captured deer to Jesus, allowed some ancient Maya beliefs and traditions to survive, somewhat adjusted, under the cloak of Christianity. The people in the painting all wear the traditional dress of San Pedro la Laguna. Other dancers, dressed as tigers and monkeys, as well as the musician playing the marimba, straggle over into the first half of the second panel. |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956The Footsteps of Yesterday and TodayPanel two of a triptych: Municipal government.Oil on canvas, 2001, 30” x 40”Arte Maya CollectionThe second and third panels of the triptych deal with the local government and the Catholic Church. At the time depicted in the painting, San Pedro la Laguna and all other highland Maya towns had intertwining civil and religious governance systems organized as part of the cofradíaaas (brotherhoods). In the middle panel, the man between the two crosses is the mayor of the town. He carries in his hand a baton (vara) that is symbol of his office. Directly behind him we see the head of a man wearing a distinctive red tzute (headscarf), which is an indication that he is one of the principales (high-ranking elders) of the town. |

|

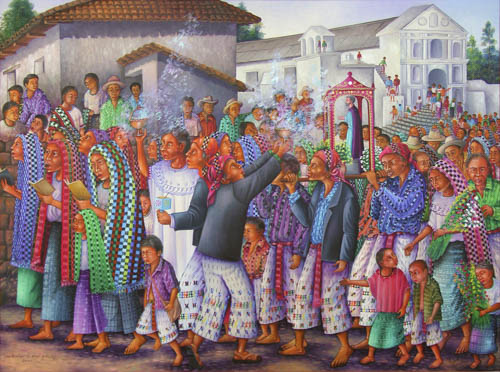

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956The Footsteps of Yesterday and TodayPanel three of a triptych: The Catholic ChurchOil on canvas, 2001, 30” x 40”Arte Maya Collection

The third panel shows representatives of one of San Pedro’s six cofradías, or religious brotherhoods. The women singing are texeles (female associates of the cofradía), followed by more principales (important male members) with incense and carrying the image of Saint Peter. |

|

Mario González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1967BonesetterOil on canvas, 2014, 23” x 32”Arte Maya Collection

A bonesetter is shown with a patient in the family’s house. A person’s dreams call them to become a bonesetter, and their dreams guide them to find a bone that becomes the special healing instrument. The healer realigns a fracture by manipulating and massaging the area of the break with this mystical bone. He then applies heated tobacco leaves to the affected area and wraps it all in a tight bandage and, when necessary, a splint. The healer believes that special bone does the healing; he or she is just the person who works the instrument. The patient may offer money or food for the service, but the healer never requests payment because his calling is sacred.

Read the Complete Text |

|

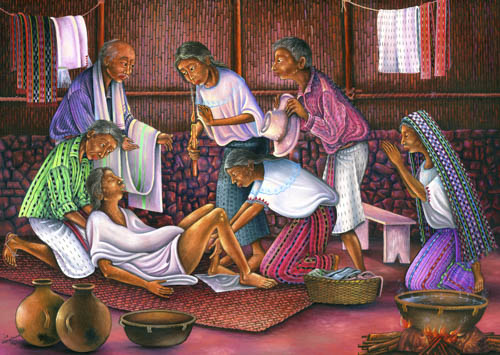

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956The MidwifeOil on canvas, 1996, 20” x 26”Helen Moran Collection

This painting depicts a birth attended by a Maya midwife—one of the most respected spiritual guides of the community. The raised shoulders of the mother indicate that she is having trouble giving birth. The interior of this simple stone and cane house reveals the life of a typical campesino family in the late twentieth century.

Read the Complete Text |

|

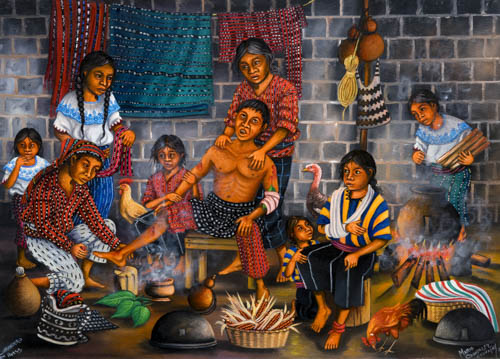

Juan Fermín González MoralesTz’utujil Maya from San Pedro la LagunaEl Parto / ChildbirthOil on canvas, 1999, 17” x 23”Arte Maya Collection

This painting by Juan Fermín González Morales depicts a birth in the home of a typical Maya campesino (farmer) family. Kneeling directly on the bed, the iyoom (midwife) assists the woman giving birth. We can see the baby’s head just emerging from under the edge of the shawl that is draped across the mother. Both women wear the white huipiles typical of San Pedro la Laguna. At the head of the parents’ bed, we see two small children asleep in a miniature bed. In the lower right-hand corner of the painting, a woman—probably a family member—prays in front of the family altar. The floor of the house is dirt, and footprints are visible—which carry both literal and symbolic meaning. The artist reveals here the footprints of generations of ancestors.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Mario González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1967Ancestral Rituals for MaximónOil on canvas, 2009, 30” x 31”Arte Maya Collection

Many Maya in Santiago Atitlán venerate Maximón (Ma’ Ximoon) as the Great Lord or the Great Grandfather. He keeps alive the ancient Maya myths and traditions by providing adaptations to the Christian religion that was forcibly imposed by the Europeans. Maximón is the Lord of fecundity who must fertilize the world during the spring equinox, a role also symbolized by the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. During Holy Week Maximón becomes Judas, whose betrayal was necessary as it enabled Christ to reveal his true nature.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Juan SisayTz’utujil Maya, Santiago Atitlán, 1921–1989DivinationOil on canvas, 1957, 10” x 12”Arte Maya Collection

Maya people frequently consult an ajq’iij (diviner or daykeeper) prior to making an important decision or taking on a large project. The woman and child in the painting are not wearing the traditional attire of Chichicastenango, so they probably have travelled some distance to consult with the day keepers from that town. The reading is done on a special, cloth-covered holy table. Seeds of the pito tree (Erythrina berteroana) and other divinatory objects are on the table. After the reading, the people asking for advice are often instructed to go to a specific sacred site to perform a special ritual.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Pascual Abaj / A Sacred Stone Named PascualOil on canvas , 1988, 11” x 8”Arte Maya Collection

A family performs a ritual at the pre-Hispanic shrine of Pascual Abaj, a dark stone bearing a sculpted face, that is located atop a wooded hill on the outskirts of the town of Chichicastenango. The family has come secretly in the darkness, bringing their offerings of candles, flowers, alcohol, and a chicken to sacrifice. They may be asking for help with a new endeavor, for the health of a family member, or possibly for a good harvest.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Mariano González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Adoration of the Rock Pascual, ChichicastenangoOil on canvas, 2001, 39” x 55”Arte Maya Collection

Maya spiritual guides (ajq’ijab’), accompanied by musicians, have gathered with a family at Pascual Abaj to offer sacrifices. Both male and female ajq’ijab’ perform ceremonies in the Mayan Quiché language, except for the name Jesus Christ inserted in the prayers. It is likely that this ceremony is to assist in curing one of the family members who has fallen ill. Pascual Abaj is one of hundreds of sacred sites where Maya rituals have been performed in secret for centuries. The sites are sacred but also gain their power from the accumulation of rituals performed there.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Day of Ceremonies in ChichicastenangoOil on canvas, 1997, 36” x 57”Arte Maya Collection

In the town of Chichicastenango, the steps outside the Church of Santo Tomás were built with stones from a Maya altar that was on the site. There are twenty steps, one for each day of the Maya ceremonial calendar. Every day, Maya spiritual guides perform rituals on the steps, but these are not permitted inside the church proper. The ajq’ijab’ performing the ceremonies are day keepers, people who keep track of the Maya calendar and the significance of each day. These steps thus constitute an important line of demarcation—the most visible place in the Maya world where a mix of both Maya and Christian traditions are practiced.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Pedro Rafaél González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1956Qab’aniikiil / Our Identity (Chichicastenango)Oil on canvas, 2013, 36” x 60”Arte Maya Collection

Elements that will be familiar from other paintings in the exhibit are depicted in this dramatic rendering. These include the Catholic church of Santo Tomas; a dancer carrying the Tz’ijolaj (sculpture of a man on a horse); cofradíaaa members with their symbols of office (varas); men carrying images of Santo Tomas and other saints; elaborately dressed men wearing plumes and capes represent Spaniards in the Dance of the Conquest; and the Palo Volador (pole flyers). In the upper right corner, a Maya spiritual guide performs a ceremony at Pascual Abaj. All of these activities occur in the context of the famous market of Chichicastenango.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Vicenta PuzulTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1970Curador / HealerOil on canvas, 2010, 18” x 25”Arte Maya Collection

In Vicenta’s painting, a mask maker holds up a mask he has just finished, and a female family member blesses it with incense. Every aspect of making ceremonial masks for a traditional masked dance is considered sacred. This mask will probably be used in a healing ceremony for an individual, family, or group—hence the title, Healer. Read the Complete Text |

|

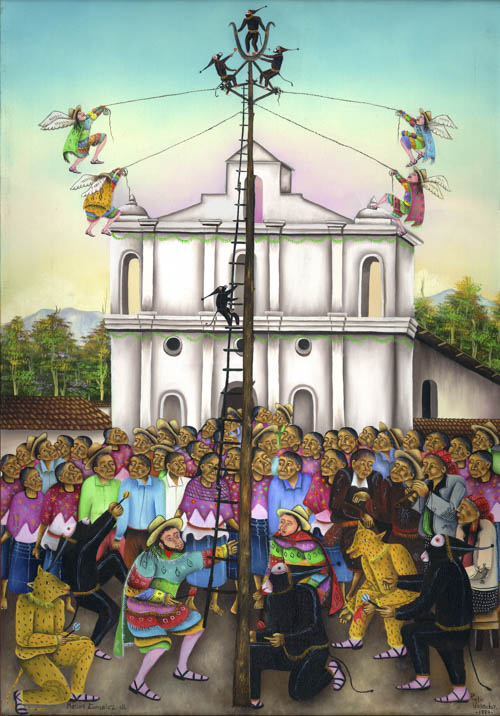

Matías González ChavajayTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1959Palo Volador / Birdman, or literally: Pole FlyerOil on canvas, 1990, 28” x 19”Arte Maya Collection

Pole flyers are a common theme in paintings by contemporary Maya artists. In this spectacular dance, men dressed as eagles, monkeys, or angels “fly” by jumping off a tall pole and slowly spinning on ropes to the ground. This dance predates the arrival of the Spaniards, and was performed in indigenous communities from Mexico to as far south as Nicaragua. When Matías painted this scene sited in Chichicastenango, it is unlikely that he had seen it performed there. He depicts four voladores (flyers) dressed as angels, rather than the two dressed as monkeys that are customary in that town today.

Read the Complete Text |

|

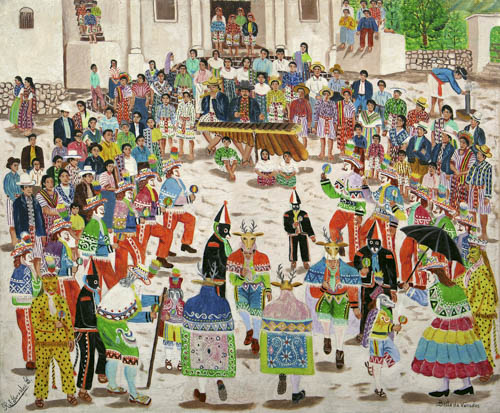

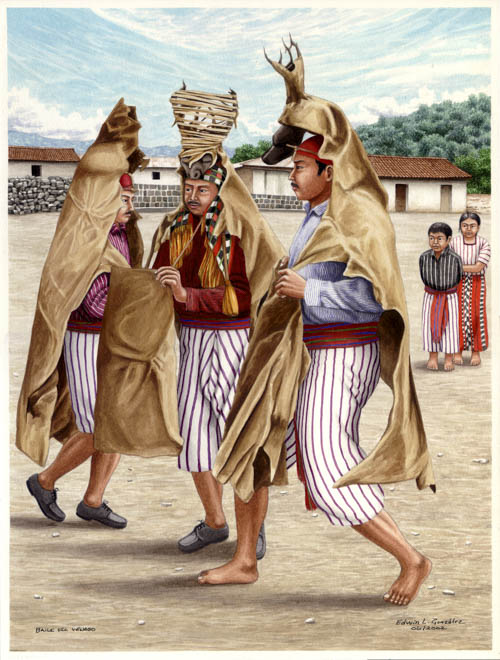

Rafael González y GonzálezTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la LagunaBaile de Venado / Deer DanceOil on canvas, ca. 1960, 20” × 24”Arte Maya Collection

The deer dance, by becoming nominally Christian in its representation, is one of the few pre-Hispanic dances to survive. The form of the deer dance varied, often depending upon the local priest’s tolerance of Maya customs. The depiction by < González y González shows the dance as it would have looked around 1940 in San Pedro la Laguna. The deer wear elaborate capes influenced by European fancy attire.

Read the Complete Text |

|

Edwin GonzálezTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la LagunaBiale de Venado / Deer DanceWatercolor on paper, 2002, 16” × 12”Arte Maya Collection

The form of the Deer Dance varied, often depending upon the local priest’s tolerance of Maya customs. In Edwin González’s painting, the performers in Santiago Atitlán dress in deer skins and wear masks to which antlers are attached. These costumes probably come close to the ancient form of the dance. Thomas Gage, a Dominican friar in Guatemala between 1625 and 1637, described the dance as follows: “These dancers are all clothed like beasts, with painted skins of lions, jaguars, or wolves …. The ancient Maya probably performed a deer dance before a hunt to ask for divine permission to kill the deer and for the safe return of the hunters.”

Read the Complete Text |

|

Emilio González MoralesTz’utujil Maya, San Pedro la Laguna, b. 1959Baile de Animales / Dance of the AnimalsOil on canvas, 2008, 17” × 36”Arte Maya Collection

During their ceremonies, the pre-Hispanic Maya often wore elaborate headdresses that represented birds and animals, and this tradition continues. Emilio’s painting Dance of the Animals is not a literal depiction of one of these dances but symbolizes something deeper—his interpretation of the spirit of the dance. His dancers are not men, but the animals and birds themselves. Read the Complete Text |

|

Diego Isaías Hernández MéndezTz’utujil Maya, San Juan la Laguna, b. 1970The Dream of IsaíasOil on canvas, 2016, 22” x 30”Arte Maya Collection

This self-portrait reveals the artist’s remembrance of his Maya heritage and his dream for the future. Isaías is among the younger generation who are proud of their heritage. The signing of the Peace Accords in 1996 opened the door to a renewed respect for Maya traditions and spiritual practices. Read the Complete Text |

|