|

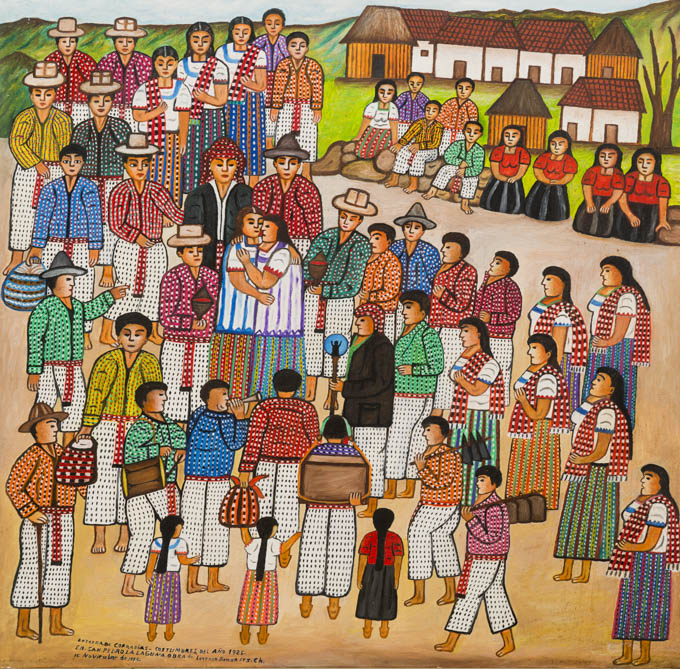

Entrega de Cofradías (Changing of the members of the brotherhood) by Lorenzo González Chavajay, 1995.

Every year there is a change in the individuals who perform different roles in Maya religious brotherhoods

known as cofradías. The outgoing official gives the power and emblems of office to the incoming official, and the pair

embrace. In this painting, officials are handing over such objects as the vara (the staff of authority); the adzes for

burying bodies; and the censer for burning incense.

In 1994, Lorenzo González Chavajay spoke about an idea for a large new painting, the one depicted here: “And the customs

of the past, I don’t want to forget them… My favorites are the customs of my town. That is what I am painting here: a texelaa’

with her candle; texelaa’ is what we call a woman in the cofradía. When the [roles in the] cofradías are being handed over,

she carries the incense. In one hand she has a censer, in the other hand a container where she keeps the incense so that when

it stops smoking, it can be started again. But with time I am going to draw such a special picture about when the cofradías

are delivered. The outgoing cofradía hands over and the incoming is like this, the representatives embracing. But [I need

to draw] a huge number of mayordomos, a huge number of texelaa’, who come together for the transfer. Some carry objects,

while others bring the flute and drums. A ton of them. This is a beautiful custom, but to draw it, I need a large canvas.

It is worth the effort. I will do it. I have to plan on doing this, if God gives me the time.” It was the next-to-last

painting that Lorenzo González Chavajay would finish before his death.

Members of a cofradía served for a year, after which time in a ceremony they transferred the power and emblems of the cofradía

to the new incoming officials. The most visible emblem, the head of the staff (the vara), displays an image symbolizing the

cofradía. In the larger and wealthier Maya communities, the heads of the staffs would be made of silver; in smaller or poorer

towns, such as San Juan la Laguna, they would be painted wood. During their year of service, the members of the cofradía would

have to give up their normal work and responsibilities and devote themselves completely to the cofradía. Family members would

take over their work during this term of service and support their family during his period. Besides devoting their time and

energy, the k’amal b’eey (the head of a cofradía) would be required to host the fiestas of the cofradía during the year.

Honor obligated the head of the cofradía to pay for the considerable costs of these celebrations, and he would sometimes

need to sell his land or family lands to meet these obligations.

In the painting two of the cofrades (male members of a cofradía) carry adzes, property of the cofradía. These are used for

digging graves. Lorenzo explains: “Before, it was the town and the cofrades that had to dispose of [the body]. But now the

cofradías don’t exist. In times past, when a person died, a cofradía was responsible for carrying the person to be buried.

The mayordomos and the six cofradías were responsible according to the day of the week that the person passed away. Mondays

it was the cofradía of Saint Nicolas; Tuesday, I believe, it was Saint Anthony’s turn; Wednesday, the Rosary; Thursday, the

Body of Christ, also known as the Sacrament; Friday, the Holy Cross; and Saturday, the Immaculate Conception. By contrast,

today, if someone evangelical dies, that evangelical church has to bury them. Now if you die Catholic, the Catholic church

is obligated—there are always groups who are responsible. Before, it was the cofradías.”

|