|

|

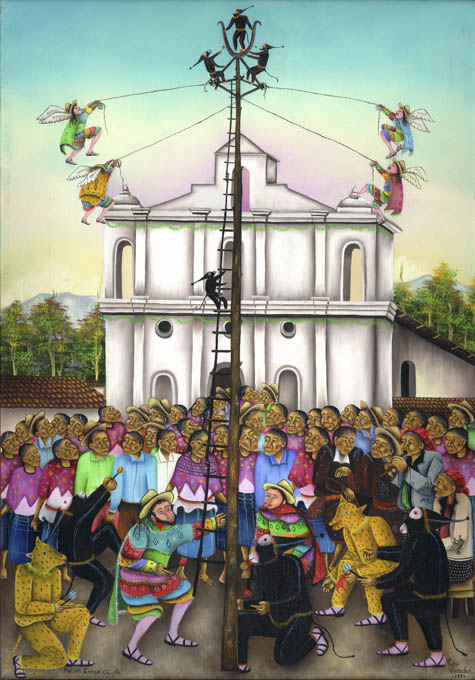

Palo Volador (Birdman, or literally: Pole Flyer) by Matías González Chavajay, 1990

In this dance men dressed as eagles, monkeys, or angels “fly” by jumping off a tall pole and slowly spinning on

ropes down to the ground. Even before the arrival of the Europeans, the dance of the Palo Volador had spread in Indigenous

communities through Mexico and as far south as Nicaragua. The Story of the Palo Volador According to the Popol Wuj

In Maya culture throughout history, scribes and artists have provided detailed accounts of great events relating

to spiritual and material connections and experiences with nature. Features of these narratives can be seen in the grand Maya

edifices and in painted ceramics dating from the pre-Classic period. The events recounted belong to the creation story of today’s

world, back when only supernatural beings existed. In one such story, brothers Junajpu and Xbalanke were destined to defeat the

Lords of the Underworld and transform themselves into the sun and moon, creating the conditions for the world as we know it. The Selection of the Tree, and the Relationship of the Flying Pole with the Popol Wuj

The selection of the tree for the commemoration or celebration of community events is very important. The tree must

be of a special height, some thirty meters: approximately one hundred feet. The whole process requires the efforts of hundreds of

men in the community. The ajq’ijab’, or daykeepers, help choose the right tree, and then make an offering with incense, candles

and marimba music to ask permission and give thanks to the tree. After felling the chosen tree in a nearby forest, hundreds of

men use ropes to pull the tree down the mountain to a road where, unlike in previous eras, a large vehicle drags the pole to the

town plaza. Before the pole is raised, another offering is made for the success of the event, and the blessing of those involved.

The foot of the pole is then set into a hole, where a rooster has been sacrificed as the main offering. The ropes are handled by

hundreds of people to plant the pole and secure it in the chosen place. The people of the town represent the four hundred youths,

as narrated in the passage from the Popul Wuj. In addition, the tree represents the support pole that Sipakna carried and placed

for the four hundred young men. The Palo Volador and its Practice in Different Indigenous Towns of Mesoamerica

The Palo Volador is of unknown pre-Hispanic origin, likely first appearing among Indigenous people of what is now Vera

Cruz, Mexico before spreading as far south as Nicaragua. Its adoption by different indigenous cultures both before and after the arrival

of the Spaniards did not mean that its purpose and story necessarily remained the same over time. The spiritual significance of the

Palo Volador differed throughout Mesoamerica. It is thought that perhaps the dance was first performed to end a drought. The Palo Volador in Maya Communities

In Guatemala the Palo Volador is still performed in some communities during their fiestas or fairs. The town of Chichicastenago

is one of the K’iche’ Maya communities most famous for the celebration of the Palo Volador. This dance is performed in Chichicastenango each

December 21, the festival of the town’s patron, Saint Thomas the Apostle. December 21, the day of the solstice, is an inflection point in the

astronomical year, a return to lengthening days. In that sense the dance represents the interrelation of life that exists under the earth

(in the underworld), on the earth, and in the cosmos; as well as gratitude to the sun, which is inherent in Maya spiritual belief. The Palo Volador in Art

The theme of the flying pole is commonly painted by contemporary Maya artists. When Matías González Chavajay painted it for the

first time, it is very unlikely that he would have seen the Palo Volador performed in the town of Chichicastenango. That would explain why he

depicts four voladores (flyers) rather than the two that are customary in that town today. It would also explain why the voladores are dressed

as angels rather than as monkeys. In some Indigenous communities during pre-Hispanic times, the voladores were dressed as birds or eagles. In

other Maya towns, the voladores are dressed as angels, and it is probably the voladores in one of these towns that Matías had either seen or,

more likely, heard about. Through his art the artist can illustrate his dreams and his thoughts, even without ever having seen such things.

Thus, the artist tries to build a reality parallel to what he imagines. Anthropologists speculate that, to preserve the ritual of the Palo Volador, some Maya communities changed the birds into angels in order to provide the dance a Christian façade. |