|

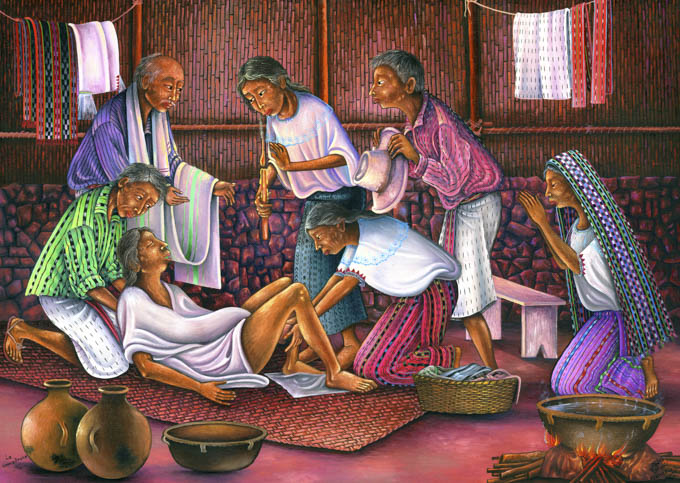

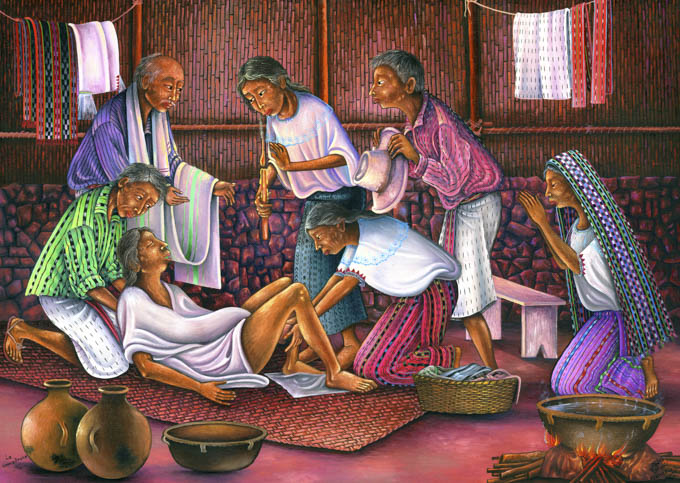

The Midwife by Pedro Rafaél González Chavajay, 1996

This painting and the following painting illustrate childbirth and the role of the midwife.

The Midwife by Pedro Rafaél González Chavajay depicts a birth. The raised shoulders of the mother indicate that she is having

trouble giving birth. This painting adds to our understanding of the life of a typical campesino family in the late twentieth

century. The better houses at that time were constructed of adobe, but today new houses are concrete block. Poorer families

had houses like this one, where the base was made of stone, but the walls were made of cane lashed to poles. When it is windy,

dust from the dirt roads blows into the house through cracks in the cane walls.

Maya spiritual professions include midwives (iyomaa’), also known as “the grandmother who receives grandchildren”; day keepers

(ajq’ijaa’); shamans (aj’iitz); and bonesetters (ji’ol b’aaq or wiqol b’aaq). An iyoom (singular of iyomaa’), being a member of

a Maya spiritual profession, is not permitted to charge money for her services, relying only on the generosity of the families

she helps.

Often at birth, there is a sign that a baby girl is destined to become a midwife. The parents and their midwife will recognize

this sign—a thin membrane (caul) draped over the newborn’s head and body—but they will keep it secret from others. (As with the

other spiritual professions, it is bad luck for others outside the family to know one’s destiny.) The parents will then help guide

and prepare the girl for her sacred profession, taking her every twenty days—when her birth sign repeats in the Maya calendar—to

pray to Santa Ana, the patron saint of iyomaa’ (Rogoff 2011).

As the girl grows into a young woman, she may begin having dreams that tell her of her destiny as an iyoom. She may at first resist

these dreams. But by resisting, and not going forward with what she is told in her dreams, the young woman may suffer serious illnesses.

Her body dries up; she becomes debilitated, even to the point of death. However, if she changes her mind and accepts her mission in time,

she can become revitalized physically and in her knowledge about the care of people in the community. Depending on the qualities and

energies of each midwife, this can entail great risks for her mission.

It is not an easy life for a woman. The mortality rate for births in rural Guatemala is high, and the family who has lost a child at birth

might hold the midwife responsible. Also, a midwife is on call at any hour of the day, and her husband may prefer that his wife follow a

more traditional role. In addition, a midwife needs to refrain from sexual relations in the days before a birth, and this can cause problems

with her husband (Paul 1973).

The young woman usually resists her calling until someone in her family becomes gravely ill. She then learns in her dreams that sickness and

death will result if she resists her destiny. The spirits of previous iyomaa’ visit her in dreams and, when she accepts her destiny, they teach

her the skills she will need in delivering a baby. They also teach her the prayers and rituals necessary for her profession, and reassure her

that they will always be with her in her dreams.

An iyoom needs an understanding of the Maya calendar, to inform the parents of the child’s ch’umilaal (day or star of birth) so they can raise

their child with respect for his or her abilities and destiny. At birth the iyoom may see signs that a child has a special spiritual destiny

as an ajq’iij (day keeper), an aj’iitz (shaman), wiqol b’aaq (bone setter), or iyoom. This information she will impart to the parents, so they

can guide their child carefully (Rogoff 2011).

Paul, Lois. 1973. “Careers of Midwives in a Mayan Community” in Women in Ritual and Symbolic Roles. Edited by Judith Hoch-Smith and Anita

Spring (Plenum Publishing Corporation, 1978).

Rogoff, Barbara. 2011. Developing Destinies: A Mayan Midwife and Town. New York, Oxford University Press.

|