Chapter Two

Sudden Daylight

The long noche negra ended as suddenly as it had begun twenty-five months earlier when Francisco the

baker was kidnapped. On October 28, 1982, a company of military men crossed the lake in two launches and arrested

Jacinto, Adolfo, and five other commissioners. This swift operation put a sudden stop to kidnappings, threats, and

demands for money, as well as signs of purported guerrilla activity: shots in the night, slogans on walls, provocative

leaflets. To be sure, only some of the evil commissioners were hauled away while other members of the gang remained at

liberty, but that was enough to restore peace to San Pedro—for just over two years.

Why the military command decided to crack down when it did, turning against the same two top-level commissioners it had

found innocent of Fernando's charges only three days earlier, or why the military struck at all, given its record of

repeatedly ignoring complaints, remains a matter of conjecture. At what level was the decision to strike made? Was

there a change of heart or of military commanders?.

One woman in San Pedro attributed the crackdown to information she supplied. She was a seamstress who traveled to different

places to sell her goods, like the seamstress who was killed in a neighboring town. Jacinto and Adolfo had told her that

she was suspected of taking food to the guerrillas and was on a blacklist but that a payment of three hundred dollars plus

sexual favors would save her life. With great difficulty she raised the money but decided that before handing it over she

would make inquiries directly at the army post. She did this on the advice and with the help of an intermediary in Santiago

Atitlán. When she asked a major at the post to whom she should give the money to get her name off the list, he said that

she was on no list and asked her to name the Pedrano commissioners who were demanding payment. She did. She thinks, as do

some others in town, that what she revealed at the base played a significant part in getting the military to make the

arrests..

Many believed that the decision to strike was made at a higher level. Five or six months had elapsed since Antonio made

three trips to the city in what seemed at the time to be a vain effort to persuade Ríos Montt to act on the community's

request for intervention. In retrospect, however, it was thought that the president was only biding his time until he

could rotate or rein in his field officers and that the crackdown on the commissioners was his delayed response to the

petition Antonio had delivered or perhaps to the demand submitted by the permanent force. Others thought that the president

was moved to act by the telegrams he received from Fernando, his one-time political supporter..

Still others had reason to believe that the decision to end the town's suffering was made at a yet higher level. The bereaved

father who admonished Jorge, the mayor, to repent, told us that after his son's abduction he and the pastor of his church, the

Assembly of God, prayed day and night for one month until, finally, the commissioners were arrested..

In point of fact, there were two military posts across the lake, the army post outside Santiago Atitlán, and a naval station

near Cerro de Oro, a hamlet of Santiago Atitlán. The arrest was made by marinos (navy men) traveling in naval launches. It is

not clear whether the commanders of the two military posts acted separately or in concert or in response to orders from above.

Just before making the arrest, a lieutenant from across the lake went about the town soliciting testimony from some of the many

Pedranos who had been threatened or victimized by the commissioners. The lieutenant then went to the municipal headquarters.

Mayor Jorge, accompanied by Chief Commissioner Jacinto, was away on a mission of some kind. But, as in all such cases, the

vice-mayor was on duty, and he later recounted what happened that day. The lieutenant, who was working under orders from Rios

Montt to be very severe (in the opinion of the vice-mayor), demanded to talk to a certain commissioner, who happened to be seated

with a companion in the municipal office. The two commissioners greeted the lieutenant cheerily: "How goes it, chief! What is

your wish?" The officer whirled around and hissed at them not to move. He and his men then proceeded to round up the other

commissioners, including Jacinto, returning from his trip. Under the ceiba tree shading the town square, the officer shouted

at the men in chains that they were the real guerrillas who had been operating in San Pedro.

|

| The ceiba tree that used to shade the town square in San Pedro. A market and basketball court now occupy the space.

Painting by Chemz Cox, 1998.>br>

The seven captives were taken to the military base near Santiago Atitlán, where they remained ten days while

confessions were extracted from them. On November 7. 1982, they were taken back to San Pedro for complaints to be presented.

The prisoners appeared haggard and beaten. A thousand or more people assembled in the central square. About twenty heavily armed

soldiers guarded a cleared space between the crowd and the municipal building. Over a loudspeaker set up for the occasion, a

spokesman explained that the military was there to protect, not to threaten, people and that anyone seeing something wrong

should tell the military authorities about it. The speaker added that civil patrols would soon be organized in San Pedro.

The captives were held incommunicado in the local jail for four days, and then taken to Sololá. The families of the arrested

men, like the families of their earlier victims, sought desperately to locate captured relatives. In January 1983 we received a

letter from one of Marta's younger sons, the only truly literate member of the family. He was working as a teacher in a remote

hamlet of Uspantán, in El Quiche. After returning from a vacation in San Pedro, he wrote to describe the sad situation he had

witnessed in Marta’s household. His account can be paraphrased as follows:

My mother is sick and depressed because my brother Adolfo is now one of the seven prisoners. I wasn't there at the time of the

arrest and don't know just what happened, but everyone turned against the commissioners, condemning them in many testimonials filled

with slander and false accusation. A document denouncing the commissioners was taken to the military post at Santiago Atitlán, and

the men were arrested that same day. After suffering for nearly a fortnight at that post, they were handed over to the mayor of San

Pedro, but he did not want to try their case. They were then transferred to Sololá, but the judge there didn't settle anything.

They were then shifted to the capital, but we don't know where.

My mother grieves, not knowing whether Adolfo is dead or alive. She suffers from bilis (bile attack) and hovers near death. We were

sad during Christmas and New Years because a member of our family was missing. Adolfo's wife, my sister-in-law, is all undone. Together

with my mother, she weeps day and night. Only God knows what's happening to Adolfo.

A month later Marta wrote to say that she had learned where the prisoners were kept in Guatemala City. They were in the custody of the

Second Corps of National Police. Adolfo could be set free, she wrote, in exchange for $400, a sum utterly beyond impoverished Marta’s

means. She did not say who was the source of this information, but two months later, in April 1983, when we visited San Pedro, we were

told that the source was Mario, the güizache with an unsavory reputation who had earlier gone with five others to the commander of the

post in Santiago Atitlán to accuse Fernando of slander.

None of the seven former commissioners was released. In fact, in January 1983 they were joined in jail by an eighth former commissioner,

who had been arrested on new evidence implicating him in murder. He was accused of stuffng sand into the sack used to sink the last man

seized by the imprisoned commissioners. The town waited for the prisoners to be sentenced, worried that the culprits would return and

again terrorize the town. But the people did not sit still. A four-man delegation traveled to Guatemala City to present a petition to

President Rios Montt, giving an extra copy of the document to the editors of the newspaper Prensa Libre.

\

On April 12, 1983, the newspaper ran a story on the contents of the document, listing the names of the eight former commissioners and

their crimes: theft, kidnapping, extortion, blackmail, rape, abuse of power, and others. According to the newspaper, "about 8,000" Pedranos

(an overgenerous estimate of the town's population) demanded trial without further delay and swift application of the death penalty.

The petition, said the newspaper, also named and demanded the arrest of ten additional suspects "who are still going about freely as

though they hadn't done a thing." The Prensa Libre article also carried a photograph and listed the names of the petition-bearers. One

of those pictured, the leader of the four-man delegation, was a man named Pedro, who was to distinguish himself—and imperil his life—as

an indefatigable foe of the criminal commissioners.

The eight prisoners continued to be transferred from one locality to another. From Guatemala City they were moved to Quezaltenango. By

the time we visited San Pedro in April 1983, they had been moved again, this time to Huehuetenango. Months elapsed, and the prisoners

still were not tried. In an effort to win freedom they resorted to a wily stratagem. Rios Montt had offered amnesty to subversives who

turned themselves in, and Mejía Victores, his successor, repeated the offer. On August 12, 1983, only days after Mejía Victores assumed

power, the eight prisoners signed a petition addressed to the new president, claiming that they had been members of a guerrilla faction

called "lxim" and had been "100 percent subversive." They were responsible, the petition stated, for murder, blackmail, rape, and other

criminal acts but were now determined to reform their ways and become loyal and productive citizens. Their request for amnesty was not

granted.

After the arrest of seven commissioners, including their chief, in October 1982, one of the remaining commissioners, Salvador, took over

unofficially as acting chief. His companions tried to have him named official chief of a fifteen-man slate of military commissioners they

proposed. The Sololá military commander accepted their proposal, but the town objected vehemently to Salvador and his cohorts. At a meeting

with the commander, veterans making up San Pedro's permanent force shouted down the commander's list and insisted that he endorse their own

list of fifteen, with a chief other than Salvador. The commander backed down, accepting the town's new slate. The new chief military

commissioner promptly sought to gain the community's confidence by making the rounds of all the churches in town to vow that he would defend

his community.

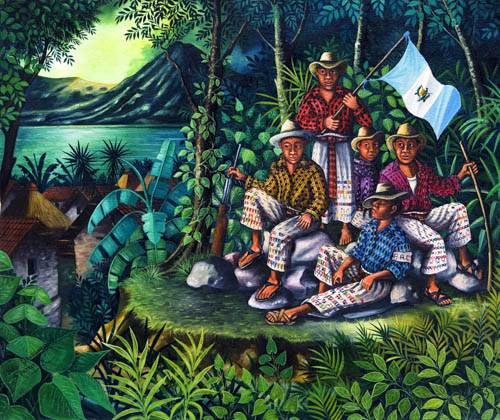

|

"Nos Obligaron a Patrular," we are obligated to patrol. During the time of violence, in addition to the military, the government of Guatemala

required able body men to patrol areas of Guatemala. Painting by Mario González Chavajay, 2007. Collection: Rita Moran:

mayawomeninart.org

With a trusted complement of commissioners in place, Pedranos at last consented, late in November, to organize a "voluntary" civil

patrol system consisting of all able-bodied men between the ages of eighteen and fifty, a force of more than 1,000 divided into squads and platoons

with rotating on-duty assignments. Before the change of commissioners, Pedranos had resisted pressure from the army to institute a civil patrol system.

In San Pedro, as elsewhere, the civil patrol serves under the command of the chief commissioner, who takes his orders from the army command in Sololá.

The new chief commissioner was replaced after about a year of service because of personal shortcomings: he had a weakness for women and drink. On

October 5, 1983, he was succeeded by Lencho, a thirty-four-year-old Pedrano with an unimpeachable character, who was to sacrifice his life in the

service of his community.

As 1983 drew to a close, five more former commissioners were arrested, four of them among the ten named in the April 12 newspaper article as

collaborators still at large. They were detained in Sololá but were released after a fortnight. Another, more enduring year-end development was the

dismissal of Jorge from the mayor's office by a colonel named Rébuli, who assumed command of Military Zone 14 on November 1,1983.

Colonel Rébuli was asked to attend a meeting in San Pedro to hear complaints against Jorge, who was accused of being party to the plans and crimes of

the former commissioners. It was pointed out, for instance, that before one abduction Jorge told the prospective victim that he was on the blacklist

and would be killed. Realizing that the town was rebelling against the authority of a leader who worked against their interests, the commander told

the mayor: "Jorge, the town doesn't want you any more. Resign!" Jorge did so.

Colonel Rébuli was well regarded in San Pedro not only because he had agreed to make Jorge step down but also because he had seen fit to send a

one-hundred-pound sack of black beans and five sacks of corn to each of the widows of kidnapped Pedrano men. Unfortunately for San Pedro, Rébuli

did not live long enough to authorize the appointment of Jorge's successor. On November 20, 1983, the colonel was killed in an ambush near Cerro

de Oro on a side of the lake distant from San Pedro. To replace Jorge, the town had installed a mayor they could trust, but after one week of

service he had to vacate his office to make room for the Pedrano selected by authorities in Sololá. With the untimely death of Colonel Rébuli,

the conspiring supporters of the deposed mayor apparently could exert enough influence in Sololá to block the appointment of a person who would

be their enemy. The mayor selected by Sololá was the man who had been vice-mayor under Jorge and who had assumed office at the same time (June

16, 1982). He became mayor on December 3, 1983. Most townsmen did not think he had collaborated with the evil former commissioners, although

some citizens had reason to believe that he would be less than forceful in pressing the town's case against the criminals still walking the

streets.

Colonel Rebuli was presumably killed by guerrilla forces. The ORPA guerrillas took credit for the action, claiming in a publicity release that

the deed was in retaliation for the fierce counterinsurgency campaigns the colonel had launched in the departments of San Marcos and Quezaltenango

before his appointment as commander of the Sololá military zone. Nevertheless, some Pedranos suspect that Jorge and his cronies had a hand in

Rébuli's assassination.

The year 1984 passed without major incident, thanks to the determination and unimpeachable character of Lencho, the new chief commissioner. In

sharp contrast to the imprisoned Jacinto, who had used his position to prey on his own people, Lencho was unswervingly responsive to the interests

of his community, to his Protestant church (Pentecostés de America), and to his wife and three small children. He divided his time between work

in the field and his official duties. Each day he mustered the men on civil patrol duty. Periodically he traveled to Sololá to report to a

lieutenant named Rolando, his contact in military zone headquarters. Members of the old gang still at liberty tried to draw him into their

orbit, to make him play their game. They tried unsuccessfully to extort three hundred dollars from him. Antagonized by his rectitude, they

sought ways to undermine his standing with the army. "If they kill me, let them kill me." Lencho told his townspeople.

Since he was not paid for his service as chief commissioner, Lencho had trouble meeting the cost of traveling to Sololá by launch and bus. He

had been orphaned at an early age, had inherited little land, and always had to work hard for a living. The permanent force, realizing that

in Lencho the town at last had found a staunch defender, suggested that each member of the civil patrol contribute five cents a month to pay

Lencho's transportation costs. Out of the fifty dollars a month thus raised, Lencho was given seven dollars each time he had to make an official

trip. Salvador, piqued that he had been rejected as chief commissioner after Jacinto was arrested, informed the military intelligence unit in

Sololá that Lencho was illegally taxing the personnel of the civil patrol. Lencho was summoned to Sololá for questioning. Although the military

officers seemed to accept his explanation that the idea of a collection was not his but that of the permanent force, he resolved nevertheless

to accept no more money for trips.

When Lencho was asked to turn in allegedly subversive Pedranos, he refused to cooperate without proof of culpability, pointing out that killing

an innocent person went against the word of God. His protective policy, which won no favor with the military forces or their local collaborators,

was demonstrated in December 1984 when soldiers arrived from Sololá to seize a certain Pedrano. The soldiers woke up Lencho late at night, ordering

him to turn the man over to them, it being the responsibility of a town's chief military commissioner to approve an army arrest order. Lencho

would not sanction the order, insisting that a hearing must be held the next day to consider charges and evidence. The inquiry that followed

revealed a chain of events that began with Marta and her daughter-in-law, the women who had wept together during the 1982 year-end holidays

when the whereabouts of Adolfo, their arrested son and husband, was unknown. The episode throws a shaft of light on the kinds of behind-the-scenes

motives and maneuvers that can prompt "disappearances."

Marta knew from the start, of course, that her son Adolfo was a military commissioner. But for months she was apparently unaware that the commissioners

were involved in the kidnappings. Her letters had expressed shock at the abduction in September 1980 of the baker Francisco and other abductions

that followed. After mid-1981, however, she ceased writing. The tavern quarrel between Adolfo and his brother-in-law that resulted in the latter's

death occurred about six weeks after Marta's last letter. In mid-1982, after a year of silence, she wrote again to say that she was deathly ill,

but the letter made no mention of the continuing string of kidnappings or the murder scandal involving her son Adolfo.

For more than a year following the arrest of Adolfo and other commissioners, Adolfo's wife and two small children continued to live in their tiny

cane-walled hut adjoining Marta's house. The two women shared their meals and their sorrows. But at the end of 1984, Adolfo's wife became interested

in another man, who had courted her before she married Adolfo. Marta flew into a rage on discovering the lovers alone in a closed room. The younger

woman left Marta's home and took up residence in her parents' compound. Marta, possibly encouraged by former associates of her imprisoned son, sought

out a military officer temporarily in town to denounce the man who had stolen her daughter-in-law's affections. Marta claimed that he was a subversive.

And that is why soldiers woke up Lencho one night in December and told him to order the capture of this supposedly subversive Pedrano.

The ensuing inquiry disclosed that the army was acting on derogatory information supplied by Marta. Called in to explain the basis for her accusation,

Marta told the investigating officer that the man delivered food to guerrillas hiding in the hills and held guerrilla meetings in his house. When asked

how she knew these things, she replied that she got the information from the man's seven-year-old daughter while she and the girl were washing clothes

on the shore of the lake. The girl was summoned and swore that she had never said what Marta claimed she had said. It developed, moreover, that the two

customarily did their washing at different locations on the lake. Lencho and others testified that the accused man was a good worker and a law-abiding

citizen. With no proof that he consorted with guerrillas, the case against him was dropped

Lencho's determination to protect the lives of innocent Pedranos did not please collaborators of the imprisoned commissioners, who, therefore, accused

Lencho of supporting the guerrilla cause. Military authorities confronted Lencho with the fact that he was not turning in anyone from San Pedro. He stood

his ground, asserting that the accusers lied and that no man should be condemned without a hearing.

While Lencho was earning the people's gratitude for courage under pressure, his elderly uncle Pedro was leading a struggle to prevent the eight prisoners

from being set free. As indicated earlier, Pedro had led the four-man delegation that gave the newspaper a copy of the town's petition urging Ríos Montt

to speed the trial of the arrested former commissioners and to effect the arrest of ten additional suspects named in the document. For a long time the

prisoners were shunted from one city to another without trial.

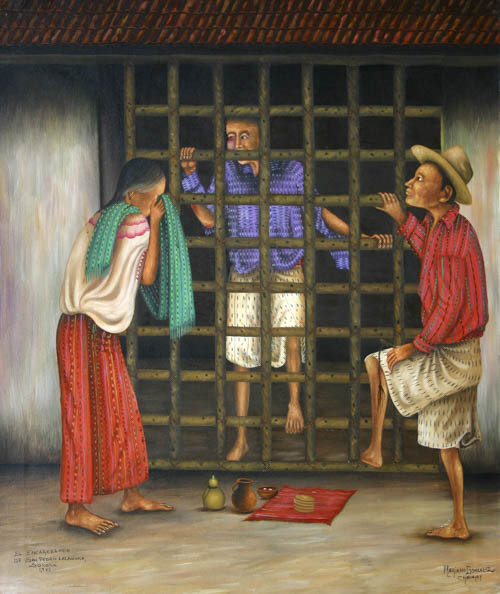

|

"El Encarcelado de San Pedro la Laguna," (a prisoner in San Pedro la Laguna) by Mariano González Chavajay. The families of jailed people are

responsible for providing food. Collection: Arte Maya Tzutuhil.

Finally on February 28, 1984, sixteen months after they had been arrested, their sentences were pronounced. Jacinto, who had been chief military

commissioner, was sentenced to serve twelve years in prison; Adolfo, second-in-command, ten years; the six others, two to four years each. The convicted men

were committed to the Cantel penal colony near Quezaltenango. They had served only a fraction of their time, however, when rumors began to reach San Pedro

that they would soon be released. To forestall this unwanted development, Pedro, the indefatigable foe of the former commissioners, traveled repeatedly to

Sololá, presenting evidence and submitting documents designed to persuade authorities to keep the culprits safely locked up.

Such was the situation through the end of 1984 and the beginning of 1985—Pedro fending off efforts to set the prisoners free, his nephew Lencho fending off

attempts to capture alleged subversives—when a tragic blow rocked the town. Nephew and uncle were seized and brutally murdered, their corpses discovered

at dawn on Wednesday, February 27, 1985.

|