The Paintings of

Juan Sisay

Artist Biographies

Santiago Atitlán

Juan Sisay

Pedro Miguel Reanda

Salvador Reanda Quiejú

Elva Vazquez

Juan Sisay

By Joseph Johnston

Juan Sisay, was the first painter from Santiago Atitlán. Like most Tz’utuhil Maya, he came from a poor campesino family. He worked carting things to market on his back and as a day laborer in other people’s fields. In 1947 when Sisay was in his mid-twenties, he encountered a tourist in the plaza painting a picture of the church. When the artist finished his painting, he gave Sisay some of his paints. With these paints Juan Sisay completed his first painting, eighteen years after Rafael González y González did his first painting. Sisay sold this painting for one dollar, quite a lot in those times (Dary 1998). This sale motivated him to continue painting because it was an easier way to earn money. Santiago Atitlán is one of the places nearly all Guatemala tourists want to visit. By waiting for tourists as they disembarked from the boats at the docks, Sisay had a ready market for his paintings. Entirely self-taught, Juan Sisay initially worked in tempera on paper before switching to oil on cavas.

Juan Sisay quickly gained fame within Guatemala for painting the traditions of Santiago Atitlán. He had his first exhibition in 1957. In 1960 General Miguel Ydigoras Fuentes, then president of Guatemala, bestowed on him the Order of the Quetzal, the highest civilian honor in Guatemala. The story goes that the general wanted to honor a self-taught indigenous artist with the medal and a trip to the United States. The decision was between Rafael González and Juan Sisay. Rafael recalls the decision: “I would have gone to the United States, but the General did not like my name, my last name: ‘There are not any González who are Mayan, this last name is Spanish’” (Gomez Davis 1988) Rafael’s story, however, doesn’t take into account that the General may have liked the paintings of Juan Sisay more. Sisay’s sense of composition was simple and direct, a fact that made his style of painting appealing to the people who bought his paintings—people who also appreciated modern art.

During his trip to the United States, Sisay exhibited his paintings in San Diego. While there, he took classes in painting and drawing. His style grew more sophisticated, yet never lost its charming quirkiness. It is likely that during this trip he was encouraged to paint specific individuals rather than the generic figures that had peopled his paintings up to then. Recognizable likenesses of people who lived in Santiago began to appear in his paintings. Two of Sisay’s sons who would become painters amplified this aspect of their father’s paintings. They became notable for painting larger-than-life-size portraits of the people of Santiago Atitlán.

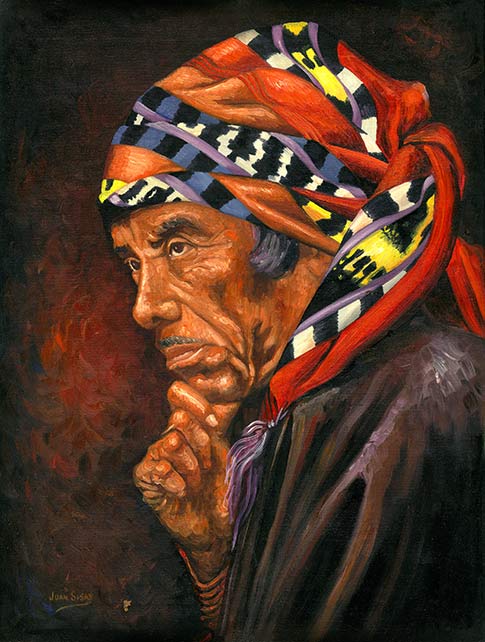

Juan Sisay multiple versions of this "self portrait" of Juan Sisay were created. Most of them were probably painted by his apprentice and then son-in-law Miguel Chavez and then signed by Sisay. The man who sold me this painting claimed to have bought it directly from Sisay himself just days before Sisay was assasinated in 1990.

By the early 1960s people regularly visited Santiago Atitlán hoping to buy one of Sisay’s paintings. Sometimes they arrived when he had no paintings, or they wanted something different from the paintings that were available, so in those cases they would commission him to do a painting. When a Tz’utuhil Maya artist receives a commission for a painting, the artist usually asks the client what theme they want him to paint, and then he paints that theme.

In 1963 Sisay recieved several commissions for paintings to be completed about the same time, but he was having trouble drawing one particular theme. Sisay thought he could meet his deadline if he someone could help him complete this drawing. He asked his priest if knew anyone who might be able to do such a drawing for him. The priest had previously encouraged fifteen-year-old Manuel Reanda to draw because he had recognized that the boy had talent, so he put Sisay in contact with Manuel. Manuel finished the drawing on canvas in one day. Sisay was so pleased with it that, rather than painting it himself as he intended, he had Manuel paint it. Sisay then signed the painting, and gave it to his client.

This began a five-year relationship where Manuel painted for Juan Sisay. Sisay would give Manuel themes, oversee the work, and sign the painting. Sisay did all the marketing. Sisay continued getting more commissions than the two of them could handle, and so he again asked the priest if he knew any artist to assist him. The priest recommended another teenager, Miguel Chavez. Manuel Reanda helped train Miguel Chavez, and as a result their work at this time was very similar to each other’s, although different from that of Sisay. Manuel Reanda and Miguel Chavez—both better draftsmen than Juan Sisay—went on to become two of the town’s best painters, but they lacked Sisay’s unique touch. Miguel would eventually marry one of Sisay’s daughters and would work with Sisay until Sisay’s death. Manuel Reanda worked for Sisay for about five years before setting out on his own.

At that time, the highlands of Guatemala were still quite isolated. People did not have television or telephones. It seems questionable that Juan Sisay understood that when he signed the paintings done by his apprentices, that his clients thought that he had done the paintings. Certainly the teenagers did not understand this. When I spoke to Miguel Chavez about this, he was truly embarrassed about it. Although he sometimes signed his own paintings, he continued working with Sisay until his death. Sisay was his father-in-law; Sisay was the person who knew the clients and marketed the paintings; and some of Sisay’s clients preferred the paintings done by Miguel Chavez (signed by Sisay) over those that Sisay painted. It would have caused trouble in the family if he had refused to continue painting for Sisay. I suspect this deception began innocently, and only after people wanted his paintings in the apprentices’s style, Sisay learned that it was wrong.

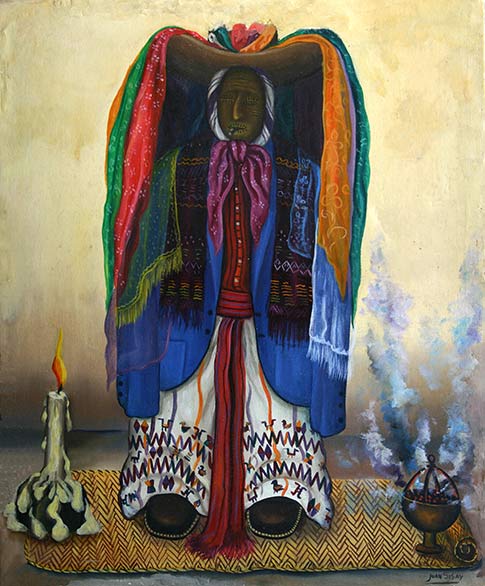

This painting of the adoration of Maximón signed by Sisay was in the collection of Maria Marta Herrera, who came from a prominent old Guatemala family. Maria Marta started the Maya group Kusamej Junan in San Francisco and that is where I saw it in her house. I lhad a copy of a thesis a German woman had written about five artists in Santiago Atitlán, including Juan Sisay and Miguel Chavez. The thesis included a black and white copy of this painting, but in the thesis it was tthe painting Miguel Chavez had been working on at the time. It was unsigned in the thesis photo in the photo. Sisay signed it and sold it to the Herreras as a painting he had done.

In 1969 with the help of Miguel Angel Asturias, who was at that time ambassador to France, Juan Sisay sent 42 of these jointly-created works to be exhibited at the Latin American House in Paris.1 These paintings then traveled to Cannes, where, among painters from fifty-four countries, he won first prize. Manuel Reanda claims that all of these paintings sold except one—the only one that Sisay himself painted.

Juan Sisay’s fortunes improved as Americans and wealthy Guatemalans bought his work. During the 1970s, every American expatriate wanted to own a Sisay. He was able to do things that most Tz’utuhil Maya could not: he sent his sons away to school, and built a large new house with an elaborate carved door.

The elaborately carved front door to Juan Sisay's house with two-headed winged birds..

In the last half of the twentieth century, the Maya highlands were changing. Shortly after the Conquest, the cofradías became part of the Catholic Church in Guatemala. These fused pre-conquest Maya traditions with worship in the Catholic Church. The Catholic Action movement wanted to rid the Catholic Church of these traditions and rituals, which it believed were basically pagan. The Maya who wanted to continue time-honored customs of the church are known as the catequistas. At the same time, the fundamentalist Christian churches made in roads in previously Catholic Maya towns. Both Catholic Action and fundamentalist Christians oppose drinking, which the Maya have used from ancient times as a part of their religious experience, in much the same way as certain native American tribes use peyote.

Sisay’s most popular, and most repeated paintings are those of Maximón, Santiago’s famous Maya folk god. Ironically, Sisay was an active member of Catholic Action which sought to rid Santiago Atitlán of these customs. In Santiago the Tz’utuhil Maya generally believe that Maximón is the creator of the universe. Maximón is cared for by the members of the Cofradía of Santa Cruz. Although now on permanent display because of the tourists who come to Santiago Atitlán, previously, at times during the year, the figure of Maximon was disassembled and stored in a loft of the cofradía house. Only the highest-ranking cofradía members have seen the body of Maximón. What people see are his outer dressings—his clothes, his hat, his scarves, and his mask. The age of this mask is not known, but it is at least at hundred years old, and probably much more. In 1950 the mask of Maximón was stolen from the loft where it was being stored. The main suspect in the theft was Juan Sisay (Tarn and Prechtel 1997). It ended up in a museum in Germany, but was eventually returned to Santiago Atitlán in 1979 through the efforts of anthropologist Nathaniel Tarn and Martin Prechtel. The theft of the mask of Maximón, whether it was done by Sisay or not, made enemies for Sisay among the devotees of Maximón.

Juan Sisay painted many versions of Maximón because it was a popular theme for the expats who bought his paintings. Judging stylistically, I would surmise that this painting must have done by Sisay himself.

For most of Guatemala, the time of violence between the army and the guerillas, lasted from 1980 to 1985. In Santiago Atitlán where there was an army base, it lasted until 1993 when, after a massacre, the army closed the base. Up until that time killings were common. Tourists still arrived on a daily basis, but people were afraid to leave their houses after dark. In April 1989, Juan Sisay, at that time head of Catholic Action, worked late into night at offices in the church, only a block from his house. When his children left their house in the morning, they found his mutilated body in the street in front of their house. Santiago Atitlán’s most famous resident fell victim to the violence at the age of sixty-eight.