Symbolic Sibling Rivalry

in a Guatemalan Indian Village

By Benjamin D. Paul, Stanford University

Introduction

I. Socialization Patterns

II. Definition of Danger

III. Cultural Assumptions

IV. Fear of Being Eaten

V. Summary

The Fear of Being Eaten

One of the most insistent symbolic themes in San Pedro culture is the fantasy of being devoured, which finds expression in a wide range of vivid imagery. It is scarcely true to claim that fanciful dangers interfere in any serious way with the daily round of San Pedro activities, which are pursued with energy and assurance, but it is hardly an exaggeration to assert that imagined dangers classically present themselves in cannibalistic shape.

The theme recurs in myth and legend. Long ago people lived on human flesh. For this they perished in the deluge which took place when the ocean rushed overland to have intercourse with Lake Atitlán, which is a female entity. But some people took refuge in safe places. These were changed into jaguars, coyotes and other creatures. The black vulture was once an angel sent out to survey the toll of human life taken by the flood; assailed by irresistible odors, he fell to devouring the corpses. Thus present animals were once human. The sun disappeared one time when he was drawn into an argument with the moon, a deceitful woman. During the eclipse, a host of tigers, lions and other fearful animals descended on the village to eat up the people, and this they will do again some day when the protective sun will disappear once more. These animals issue out of the volcano behind the village. Ordinarily they are chained down by their master, the lord of the volcano, who wields a writhing snake for a whip. All this has been seen by certain Pedranos who were lured into the volcano but allowed to leave when they resisted temptations. In times past, a monster came up from the depths of the lake. For his nightly fare he demanded the body of a child which the village authorities wrested from its parents, delivering it neatly combed and dressed to the monster at the edge of a local peninsula lest he carry out his threat to ascend into the settlement itself and eat up all the inhabitants.

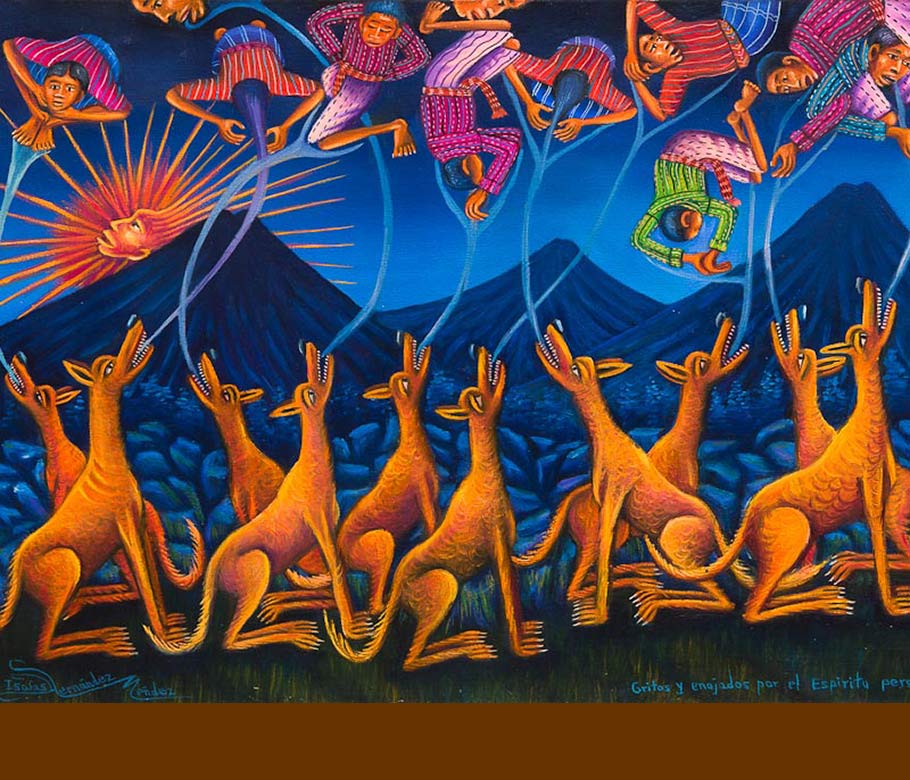

"Gritos y Enojados por el Espíritu Personal," shouts and anger of the personal spirit. Painting by Diego Isaias Hernández Mendez, 2012.

To this day certain outlying points are said to be too dangerous to serve as way stations for overnight travelers; these are places or plantations reputedly run by "Moors" with a craving for human flesh. Negroes, who are observed on the coastal plane below San Pedro, are held to be fantastically powerful; in bygone times they were not above drinking the blood of ordinary people, though "this is now against the law." In the friendliest spirit and with no apparent fear, Pedranos would ask whether it were true that an Indian would jeopardize his life by visiting the United States; they had heard that we would eat him after roasting him to a turn. Women were inclined to give this fantasy an infanticidal twist, as illustrated in the following quotation from a middle aged mother:

They say that people in the United States don't die. When they get old they become young again. But I don't know whether this is true. They also say that when the Americans have 5 or 6 children they will eat one or two, because there are so many people. How terrible to eat people! Perhaps it isn't true. They say that they put the baby in an oven and toast it well and eat it.

Once the tables were turned on several women by improvising a "they say" story to the effect that Pedranos were in the habit of eating their children in the past. This they at first denied but in the same breath reversed this stand by adding, "They say that in the past people here didn't die because there was no sickness. They ate their babies because there were so many children."

Case material on insanity in San Pedro indicates that disturbed people may strike out against property and authority, or suffer hallucinatory aggressions, or attempt to drown themselves during periods of drunken depression, They apparently do not attempt to eat people. But this does not stop others from fancying that they do. Commenting on the case of a disturbed young Pedrano who was forcibly kept home to prevent him from fleeing or committing suicide, one adolescent female asserted that he wanted to eat people. At another point she said he wanted to drink their blood, adding that this craving was characteristic of insane people. A female informant with a more lurid imagination recounted that a woman who gave birth to twins some years ago suddenly went crazy; purportedly confusing them with chickens, she placed the babies in a vessel and killed them by scalding.

San Pedro culture provides a frame of reference which relates the regulation of hunger to the danger that a baby may become the victim of its sibling's appetite. According to local explanation the food cravings of a pregnant mother originate with the fetus, which will become unhappy and leave the womb prematurely if the cravings are not satisfied. The potential knee child, who is separated from the breast during the middle stages of pregnancy when the milk allegedly turns harmful, must likewise have its food whims satisfied; it too is "eating for the fetus." To forestall miscarriage, relatives and neighbors should appease the cravings of the expectant mother and of the demanding knee child. Little is said about the appetite of the expectant father, but it is sometimes said that the food he eats also aids the growth of the unborn infant.

Social relationships with the baby are thus established before it is born. The positive side of these relationships is regularly expressed in terms of eating behavior. The negative side is likewise expressed in eating terms, destructive eating replacing productive eating. The inversion on the part of parents is represented in fantasies that "other" parents do or did devour their own babies. On the part of the knee child, the inversion is represented by the belief that under certain circumstances it feeds upon its younger sibling. Blaming another child for the death of an infant conforms to a general Pedrano tendency to displace blame and aggression downward in the social scale. This tendency is congruent with a hierarchical authority system.

It is worthwhile to consider the bearing of cross cultural comparison upon our problem. The elements of procedure, belief and assumption which enter into the ritual cure in San Pedro are not confined to that society alone. Taken singly or in partial combination, these cultural elements are common to other communities. Two comparative instances may be cited. The Mayan Indians of the Tzeltal-speaking village of Oxchuc in Chiapas believe that an individual can suffer from soul consumption and that whipping may facilitate recover.17 In that community all chiefs and elders are thought to receive the supernatural aid of an alter ego in the form of an animal (nagual) in effecting social conformity. To punish a social offender, the possessor merely allows his nagual to enter the victim's body and slowly eat its soul. Since the patient himself is at fault, he must confess his sins to recover; sometimes he has to be whipped to expiate his crime. In both Oxchuc and San Pedro one individual can kill another by eating his soul, but in the former case the aggressor acts in the public interest and the punishment is meted out to the victim rather than the aggressor, nor does there appear to be any sibling involvement.

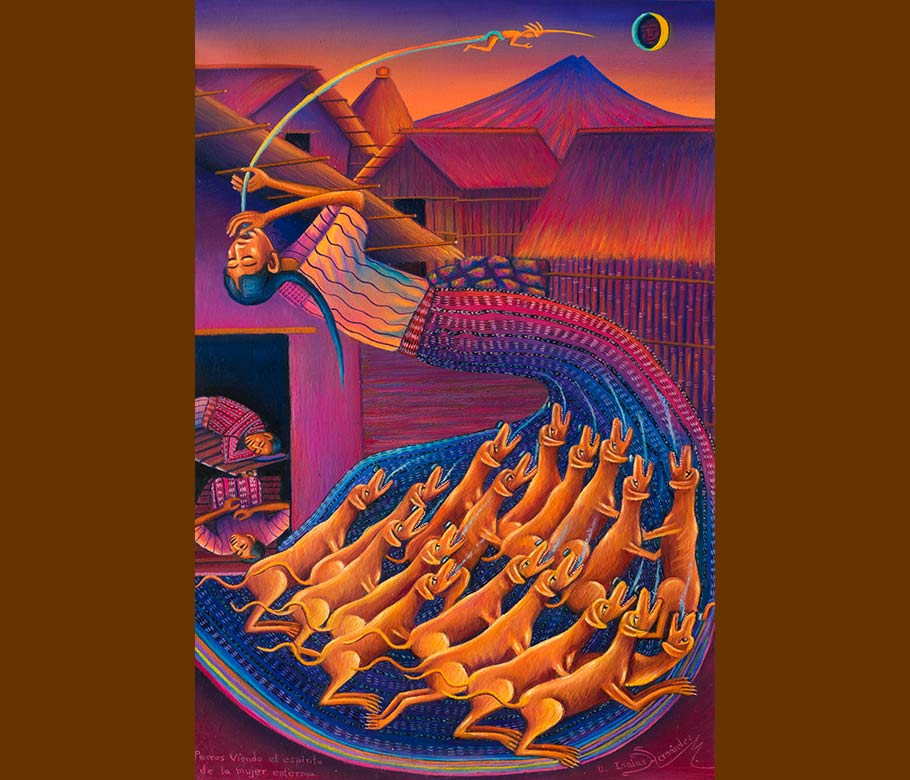

"Perros Viendo el Espiritu de la Mujer Enferma," Dogs Seeing the Spirit of a Sick Woman. Painting by Diego Isaias Hernández Mendez, 2013.

In the Mayan town of Dzitas, Yucatan, a therapeutic ritual (kex) is believed to draw off the sickness of a patient. "The kex is the discharge of a promise, made when a patient is very sick, that cooked chicken will be offered. We did not find out to whom the offering is made. The context of the ritual suggests that the offering is made to the winds that caused the sickness. ... When the patient came—generally on a Friday—Aurelia [a female curer] prayed in Maya...holding the chicken over the patient's head and strangling it to death. For a male patient a pullet was used and for a female patient, a cockerel....The chicken was immediately taken out in the bush and buried in its feathers. ...When performed for a child...an egg was substituted for the hen.”18 Here again we encounter several familiar features but in contrast to San Pedro the symbolism of punishment and interpersonal aggression is absent.

Cultural elements such as the belief that human spirits can be eaten, and the practice of killing a chicken to draw off an affliction, may have spread from one group to another by contact and diffusion. But the distributions of the respective elements overlap rather than coincide. The culture of each community includes a somewhat different assortment of the common traits. These traits, moreover, are differently combined and construed to agree with other configurations or general orientations of the respective cultures. By the nature of our present interest we have analyzed certain aspects of San Pedro culture not in terms of their areal distribution but their meaning as parts of an integrated ritual pattern.

References

17 Villa R., 1947.

18 R. and M. P. Redfield, 1940, p. 70.