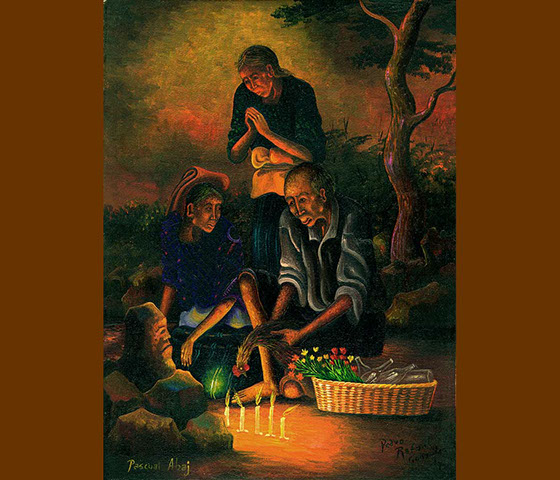

About this painting by

Pedro Rafael González Chavajay

Pascual Abaj

[A Sacred Rock called Pascual]

1988. 11” x 8”

Pascual Abaj is an ancient Maya site on a hill known as Turqa’ just outside the town of Chichicastenango where since pre-Hispanic times the Maya have come to perform religious ceremonies. The center of the site is a dark stone carved with a face. The Maya name may have been Tiox Abaj (Sacred Rock) but the site is now known as Pascual Abaj most certainly due to the arrival of the Spaniards.

The Maya ceremonies were often complex or needed to be performed on multiple days in multiple locations. The locations could include Pascual Abaj, the Church of Santo Tomás, as well as various cofradía chapels around Chichicastenango. Ruth Bunzel (1952) documented many types of ceremonies including: thanksgiving, commemoration of the dead, initiation of aj’itz (Maya shaman), invocation of one’s nagual (animal spirit), asking pardon at the beginning of an undertaking or thanks afterwards, release from one’s own evil thoughts, cure for sickness caused by a dead enemy, prayer to placate earth spirits, restoration of lost money, and sorcery against the theft of corn. Ceremonies performed today by the aj’itz—both male and female—still use the K’iche’ Mayan language. The rituals use white, red, yellow and black, candles which represent the Maya colors for the four points of the compass, and offerings such as flowers, sugar, chocolate, cakes, aguardiente (a strong alcohol), and occasionally an animal to be sacrificed. The reason for the ceremony may dictate the number and color of candles, as well as the type of offering.

Pedro Rafael painted Pascual Abaj about ten years before visiting Chichicastenango, but he somehow managed to capture both the look and feel of the place. The stone is on the far side of the summit of a high wooded hill overlooking Chichicastenango. The family in the painting has apparently decided to perform the ritual themselves rather than use a priest. Besides the candles, alcohol, and flowers, they have brought a rooster to be sacrificed, something rarer but not uncommon in the present time, since in Guatemala the chickens are usually killed by the same family who eats them.

Pascual Abaj is now a tourist site, and the rites are performed openly during the day. In earlier times most Maya, while outwardly Catholic, quietly hid their traditional Maya religious beliefs, so like the family in the painting, they visited the site in secret at night in order to avoid censure by the Catholic Church.

I have long wondered about the name Pascual. There is evidence that it could refer to the Spanish Saint Pascal Baylon, a sixteenth-century saint who became very popular in Guatemala although in a much changed form (Pieper 2002). I prefer, however, the traditional explanation of Manuel Pan Ju Lux, an aj’itz from Chichicastenago. He says that when the present church of Santo Tomás was being built in Chichicastenango, the elders were having trouble building it. The adobe kept collapsing. They thought it might be from a lack of the right ceremonies. One day a large man named Pascual came to help, but because he did not have a Maya name, they were reluctant to let him assist them. When finally they accepted his help, the building of the church progressed. At the end of each day, he would walk into the forest and disappear. One day they followed him, and where he disappeared, there was a stone. Pascual never reappeared, and from then on the elders called the stone Pascual Abaj and worshiped there.

This story would give a Christian context to this ancient site—it was the rock representing the principal builder of the local church—and it may be one means used by the K’iche’ Maya to protect their sacred place from destruction by the Spanish.

Back to Pedro Rafael González Chavajay paintings page.